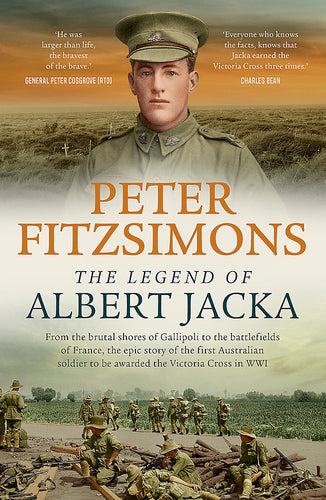

As has been his practice over recent years, this author has produced another non-fiction contribution to the world of books and literature. ‘The Legend of Albert Jacka’ by Peter FitzSimons, published in 2024, of 463 pages, including some substantial section of Notes, References, etc. This book is the story of the first Australian soldier to be awarded the VC [Victoria Cross] in World War One – that award arising from his actions in Gallipoli, and later earning many accolades for his efforts on the various battlefields of France, actions which in the opinion of many [but not his seniors] should have earned him further VC’s.

As with past contributions from FitzSimons, I found this a fascinating historical depiction of those years, though written in his inevitable style of the novel format. I must admit however, that after having already read many depictions of some of those crucial battles on the Western front in France during WWI, and now moving through FitzSimons’ vivid up-front descriptions of those campaigns which cost so many thousands of lives, often with little reward for these human tragedies, many of which could have been avoided with more competent British leadership, I’m thinking I might desist from reading about that war for the time being. Though it does seem to have been a favoured topic for the author over recent years!!

From the broadly accepted summary of the book, we read thus:

‘Our heroes can come from the most ordinary of places. As a shy lad growing up in country Victoria, no one in the district had any idea the man Albert Jacka would become.

Albert ‘Bert’ Jacka was 21 when Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914. Bert soon enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and the young private was assigned to 14th Battalion D Company. By the time they shipped out to Egypt he’d been made a Lance Corporal.

On 26 April 1915, 14th Battalion landed at Gallipoli under the command of Brigadier General Monash’s 4th Infantry Brigade. It was here, on 20 May, that Lance Corporal Albert Jacka proved he was ‘the bravest of the brave’. The Turks were gaining ground with a full-scale frontal attack and as his comrades lay dead or dying in the trenches around him, Jacka single-handedly held off the enemy onslaught. The Turks retreated.

Jacka’s extraordinary efforts saw him awarded the Victoria Cross, the first for an Australian soldier in World War I. He was a national hero, but Jacka’s wartime exploits had him moving on to France, where he battled the Germans at Pozières, earning a Military Cross for what historian Charles Bean called ‘the most dramatic and effective act of individual audacity in the history of the AIF’. Then at Bullecourt, his efforts would again turn the tide against the enemy. There would be more accolades and adventures before a sniper’s bullet and then gassing at Villers-Bretonneux sent Bert home’.

And that ‘war injury’ in particular the gas injury which basically ended Jacka’s service in the field, though didn’t stop him from seeing out the war in other relevant areas, would see him return to Australia, but be dead by the age of 39 years.

As for the horror and human waste of that time – well FitzSimons warns readers right at the beginning of this book as he introduces as to Jacka “Starting out on this book, I already had a fair idea of the sheer horror he had endured and triumphed over, given the books I had done on Gallipoli, and the battles of Fromelles and Pozieres, together with the battles of Villers-Bretonneux and Hamel. It was fascinating to research and write as I kept discovering detail that put flesh on the bones of the story and showed it in all its gory glory, its wonder, its desperation and inspiration…………Allow me to say how much I came to like and admire Jacka the deeper I went – and how amazed I was that he managed to survive, given the risks he took and the furious fire he faced. He was an extraordinary soldier……”

Meanwhile, the author and Jacka himself, back in Australia at war’s end, didn’t forget that other famous Australian military leader, Sir John Monash. While it is suggested in many quarters that Jacka did not receive additional awards of recognition for his courage and achievements under fire because he had so often being too ‘outspoken’ against some of his superiors; similarly with Monash, upon returning to Australia, he was overlooked for many roles that it was felt he had earned, and again some quarters would suggest that his Jewish background was used against him. As FitzSimons put it – “Jacka is dismayed at the lack of acclaim for the man who had saved more lives than any other Australian officer. Monash gained the eternal respect of his men simply by caring for them, and pursuing tactics that did not involve thoughtless slaughter as a starting point’ [page 380].

About Jacka, FitzSimons writes: “Happily, as I uncovered ever more about what he had accomplished, and how he had not only overcome amazing odds in battle to triumph, but also against efforts that were made against his attempts to rise in a system ill-disposed to allow a man with strong opinions on how things should be run on the battlefield to prosper” [page xiv]’

Jacka had a very similar attitude to those he served with and as a leader in the 14th Battalion – this attitude is perhaps reflected in the post-War years by the following description by FitzSimons.

[page 379] – ‘Activities with the RSL inevitably bring Jacka back into contact with Sir John Monash, which includes the two of them marching side by side every year in the annual Anzac Day marches down Collins Street. [In strict contrast to Jacko’s growing closeness to Monash is his public disdain for the likes of General James McCay, the Butcher of Fromelles as he is known, who had not only ordered his men over the top in that disastrous battle, but refused a truce with the Germans the following day that might have saved hundreds of Australian lives. When the two find themselves on the same stage for a fundraiser for the RSL, Jacka refuses to shake McCay’s hand].’

Of course there is both praise and ridicule of FitzSimon’s books, some of the latter quite harsh, for eg, two very contrasting opinions I noted recently among a series of reviews on the Goodreads website.

[1] – Peter Fitzsimons is just so good at identifying a great story, especially his books covering Australians at war, and delivering an offering that can’t be put down, brings tears to your eyes, intense pride and raises the hairs on the back of your neck. Usually simultaneously.

[2] – Sadly, a worthy subject and a life worth knowing has been let down by a writer who delights in mangling puns and similar juvenile comic effects. Rather than a proper biography it reads as an overblown piece from a weekend tabloid.

The latter writer also points out numerous factual errors that appear in Jacka – whether they can be totally blamed on the author, or more correctly on the editor/publisher, etc, remains at issue.

In a recent review within the November 2024 edition of the Australian Book Review, Robin Gerster reviews Peter Stanley’s book ‘Beyond the Broken Years: Australian military history in 1000 books’. Speaking of FitzSimons, he writes “One theme, however binds the discussion: [t]he chasm between the more astringent academic approach and the bombastic nationalism of popular writers’. Stanley is disdainful of the so-called ‘storians’, the term coined by the ubiquitous Peter FitzSimons, whose steady stream of bloated blockbusters, including Kokoda [2004], Tobruk [2006], and Gallipoli [2014], pursues a familiar nationalist itinerary. FitzSimons seeks to put the ‘story’ in war history, by writing it in the manner of a novelist and taking liberties with mere facts. That may be all right if you are Leo Tolstoy. FitzSimons is an obvious target of derision; that his brick-size books [and here’s the rub] sell so well is a trickier issue to consider”.

I guess I am one of those buyers who deserves to be a target of derision, based on Stanley’s viewpoint. So be it – while occasionally FitzSimon’s style of writing may seem a bit over-cooked, for myself, the stories depicted are a source of education which perhaps I find an easier way to ‘learn’ about events in preference to ploughing through a detailed historical analysis, which incidentally, I still do from time to time. Those of you who have read some of my past book reviews will note the range and variety of ‘historical novels’ I read ‘because’ they usually educate the reader about historical events, albeit written in the ‘manner of a novelist’ as described by Stanley.

In any case as with all genres of books – the worth of a book on any subject is in the eyes of the reader. Despite the criticism, I recommend ‘The Legend of Albert Jacka’ by Peter FitzSimons, and form your own opinion.

As for Jacka, we conclude with the words of Charles Bean [famed journalist, and later the Official Australian Historian who was embedded with the AIF during WWI] when he wrote:

‘Jacka should have come out of the war the most decorated man in the A.I.F. One does not usually comment on the giving of decorations, but this was an instance in which something obviously went wrong. Everyone who knows the facts, knows that Jacka earned the Victoria Cross three times’

Leave a comment